- Weekly Dirt

- Posts

- A very present feeling

A very present feeling

A conversation with UFO Parfums founder, Maxwell Williams.

Daisy Alioto in conversation with UFO Parfums founder, Maxwell Williams.

Today we are capping off Scent Access Memory, aka SAM, a 12-part editorial series about olfactory triggers, digital traces, mall pretzels, utopian cities, cherry chapstick, and the impressions we leave behind.

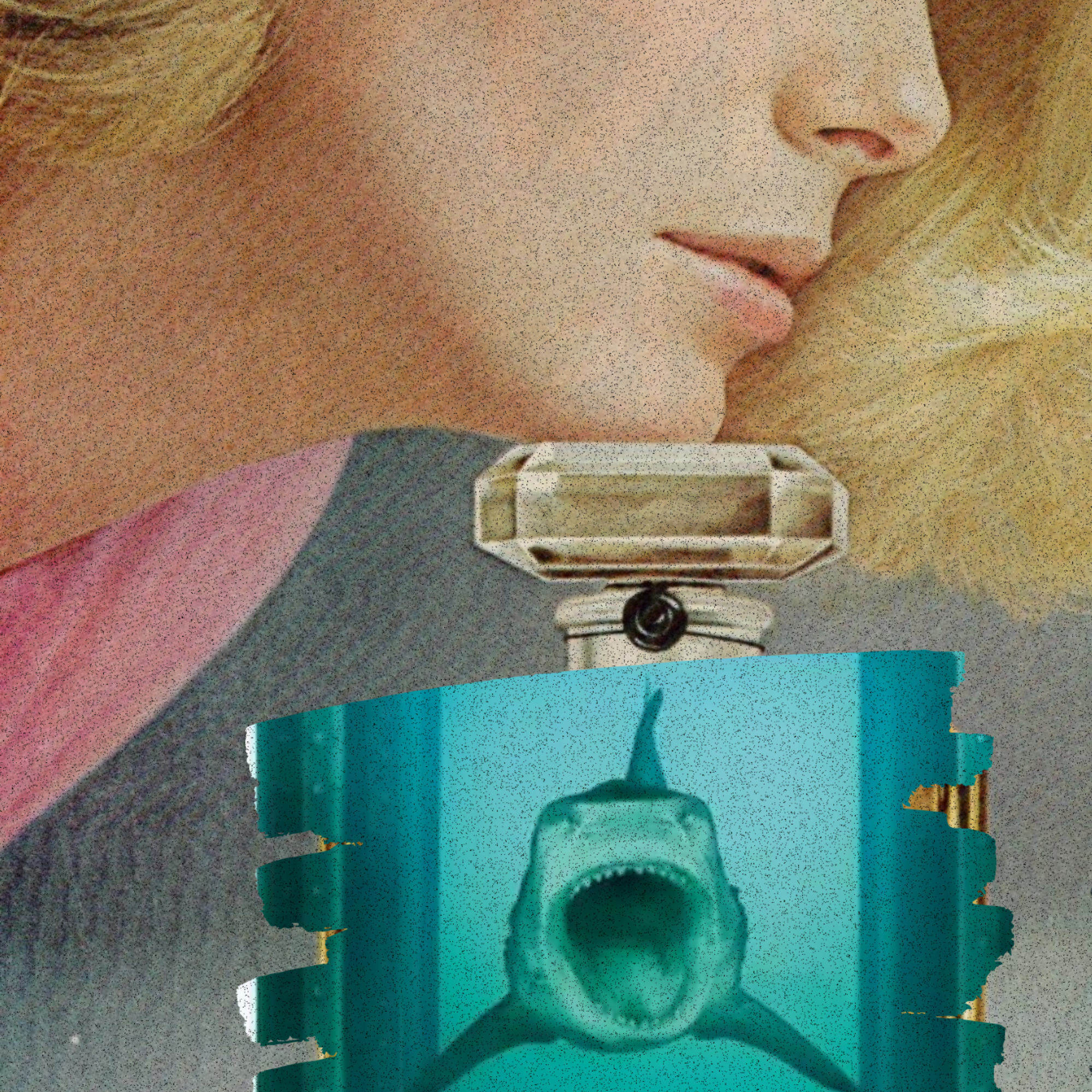

And we are pleased to introduce you to NOP, a perfume from UFO Parfums—in collaboration with Dirt and Are.na—made in the great city of Los Angeles, California.

A NOP is "no operation," an elegant architecture of empty space. Software engineers use these instructions to provide safety and balance without impacting the underlying memory. Sometimes strength is felt most keenly in absence, and sometimes the correct command changes nothing at all.

NOP is a perfume created in response to scent's relationship to memory. Created with a blend of molecules not found in nature (along with some that are, but used in unrecognizable ways), NOP pushes back against the smeller's necessity to reach into their memory centers as a reflex. NOP is meant to be a meditation of the present tense. You can pre-order it here.

UFO Parfums founder Maxwell Williams is a perfumer, olfactory artist, researcher, DJ/producer, and writer. I talked to Williams about the concept behind NOP and what it means to create a scent that can only exist in the present.

Daisy Alioto: What is your process normally for any new perfume?

Maxwell Williams: Before I answer, I just want to say I believe in a free Palestine. I’m Jewish, so it’s hard for me to talk about perfume without saying free Palestine. Free Congo, free Haiti, free Ukraine, and fuck it, I hope Taiwan stays free.

With a new perfume, it really depends. I work with a lot of different clients, and so with a client a lot of times I will ask them to work with me on developing a brief, or if they want to send me a fully formed brief they can also do that. I’m the one with the language of the perfume and they’re the ones with what they want, so I give them tips on how they can make it so I can translate what they want into the language of perfume.

When I’m working with myself, it can come from any direction. I can start with an inspiration like “I want to make a chocolate animal, I want to make a beaver that smells like chocolate.” It’ll be a dream, or some inspiration or something and I’ll be like “Oh, those two notes sound good together—let’s start there.” And then I build off of that and it turns into some giant chocolate beaver monster thing. So I don’t start with a brief for myself, I just start with general inspiration; but with a client I always work with a brief.

DA: Our process was basically briefless, but you also had such a strong idea for a concept as like an “anti-concept.” Where did that come from?

MW: One of the places that it came from is that there’s this bingo board for when I tell people that I make perfume. One of the things on the bingo board is “Have you seen Perfume: The Story of a Murderer” and another is “Oh my god, perfume and memory are so closely related.” So memory is this psychological process that is intertwined with perfume. It’s actually a real physiological process: you get the molecules and they stick to the cilia in your olfactory bulb, and the olfactory bulb translates and sends these electric messages through different parts of your brain, including parts of your memory center.

That’s basically everything, right? Memory is this physiological process that requires this present-state storing and retaining, and the part that we tend to call memory is just the retrieval of that information. So it’s encoding, storage, retrieval. I guess the concept was: what if that process was a null process? What if we didn’t store, like a computer process that does nothing i.e. the no-op or NOP function. What if we didn’t cater to memory? We don’t always cater to memory with music or optical things. Monks are always like “stay in the present” when you’re meditating. What if memory wasn’t this thing that was inherently entwined with what I was doing?

This is like a perfume about perfume, which isn’t to say I can stop memory. I can’t stop memory—that would be some sort of thoughtcrime or something—but I’m not catering to it.

So how did I approach that? With a lot of synthetic notes, a lot of molecules that aren’t found in nature, and if they aren’t found in nature, your memory of them can only be of other perfumes that happen to carry these notes. Or you can have metaphorical memories, which I guess is a different kind of memory. I’m using a lot of synthetic musks, and synthetic ambers, and things that don’t actually exist in nature. I was thinking about when people talk about “art for art’s sake” or “art about art.” This is like a perfume about perfume, which isn’t to say I can stop memory. I can’t stop memory—that would be some sort of thoughtcrime or something—but I’m not catering to it, which is sort of like the NOP process. It’s like doing something but it’s not doing something; the thing that it’s doing is specifically not doing something, and I love that paradox.

DA: As you’re talking about it and that frustration, my brain is sort of whirring around my primary occupations, which are being a writer and having what would be considered a startup. Every conversation that I have about my business needs to be tied to future potential, in the same way that every conversation about perfume has to be tied to a “future memory.” So how your present labor is always being engaged with the past, my present labor is always being engaged with the future. And the present artistry of writing is never about just the present moment. In the commercial sense you always have to think about the future reader, and you’re often, through your own relationship to the writing, engaging with the past.

So when you sent the NOP sample to me, I knew what the concept was supposed to be but of course my first instinct was to tell you what I thought it smelled like. And you had to sort of remind me—or actually you wrote in the letter to me when you sent it—“It is not meant to be deconstructed into notes/memories/metaphors, but rather a very present feeling.”

It just made me realize how much of the work that I do, whether it’s artistry or labor or a combination of the two, whether it’s monetized or unmonetized, is rarely able to exist in the present.

MW: In many languages, verbs are not conjugated for tense. So when you’re speaking one of these languages, you don’t have that same beholdenness to the past or the future. It all sort of melts together, and I feel like that is kind of the state I want to be in. I love that and I wish that I grew up learning a language like that, and I wish that my brain operated in that way in the sense that I don’t always want to be looking backwards. I have a lot of interest in dementia and what happens when we start to lose our memories, because I have a history of that in my family, and I was with my grandmother a lot when she was experiencing dementia.

Scent’s a really difficult thing to work with when thinking about how it is when we don’t have our memory. I was experimenting with the idea of “What if you brought in scents to people that were experiencing dementia” and the problem is that, actually, our sense of smell also goes away when we start to experience dementia, which is really fucking unfortunate. There’s a documentary out there (Alive Inside: A Story of Music and Memory) about people who use music to help Alzheimer's patients with recovering that sense of present-ness, which I think is so interesting because it’s using the past to achieve a sense of present-ness, to achieve a sense of humanness and autonomy. Scent isn’t able to be used that way because of the loss of smell as you get dementia. I feel like, because it is so intertwined with this sense of memory, it could really be used as a way to bring people back into the present—which is again playing around with these ideas of what our senses are and how they relate to our memory.

SCENT ACCESS MEMORY

|

|

|

|

|